CATTEDRALE EX MACELLO

VIA ALVISE CORNARO 1

BIGLIETTERIA

TUE to SUN 10 A.M. – 7 P.M.

Francesco Merlini

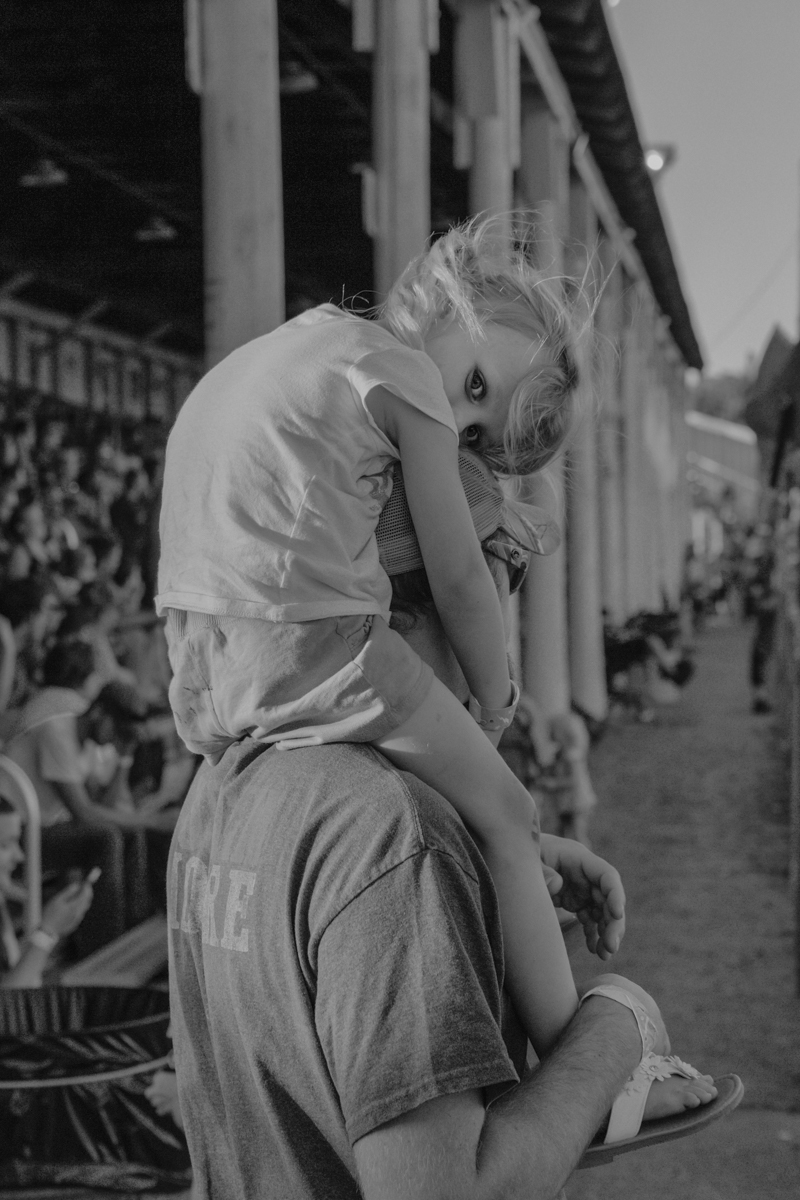

“He’s Come a Long Way That’s My Boy”

Location: USA

Ten, nine, eight – the electrified crowd chants in chorus – seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, go!

Within seconds, a flock of colorful cars that look like pieces of folk art, roars into action and start racing and crashing into one another. Demolition derby is a ritual fight to the end with a simple idea behind, elimination through destruction.

It can be a race on an eight-shape track or a derby where the last car that outlives wins. Thick clouds of blue exhaust and white steam rise, breaking the landscapes in glimpses of deafening speed like in a Futuristic painting. Families with children, old couples and motorsports enthusiasts throng the wooden bleachers and the grassy hills around the track, waiting for a spectacular crash or a fearless struggle for the victory that shows up when there is nothing left to attack. There is grace, there is violence, there is redemption and apparently there is no fear.

Even if at first glance these post-industrial liturgy have no rules, each car is carefully inspected before the show by the race officials in order to check the presence of the few requirements that guarantee an illusion of safety for the drivers. Their recklessness is supported by groups of relatives and friends who fill the pit area before every dance, helping with the last adjustments, often accomplished with a big hammer, a blowtorch and bittersweet invectives. Local sponsors, whose names are painted on the crushed bodies of the cars, allow the best maniacs to keep the cars running and enable them to attend a large number of events; Despite this, on the local level, the cost of stock car racing each week far exceeds the amount of money that can be won, making racing more a sport of love than commerce.

Beginning in the later half of 2008, a global-scale recession adversely affected the economy of the United States. A combination of several years of declining automobile sales and scarce availability of credit led to a more widespread crisis in the United States auto industry that has its heart in Michigan where more than 800.000 people lost their jobs between 2000 and 2009 as the subprime housing bubble burst, sending hundreds of thousands of homes into foreclosure as the automotive industry collapsed among the rubble, leading to the bankruptcies of General Motors and Chrysler.

This tragedy was just the recoil of something that already happened. During the 20th century the metropolitan areas of southern Michigan saw a huge and continuous increase in population and wealth because of the prosperity of car factories. Flint, for example, was the city with the highest median income in the world for young workers but at the end of the 70s, because of many reasons (the oil crises, the increase of the public transport, the competition from Japanese cars and the advent of robots) many plants shut down and the number of employees in the automotive sector plunged from 80.000 to 8.000. Flint became one of the poorest and most dangerous cities of the United States; a similar fate affected Detroit and other cities in the region.

Demolition derbies brought me in the areas of this state that have been hit by this financial and social tragedy, traveling from the suburbs of semi-abandoned industrial cities of the south, already strained by decades of racial injustice, towards the rural areas of central Michigan, a promise land for those who left the urban ruins and now a fertile land for extreme right ideals and politics. These events take place all over the United States and especially in its inner and poorest areas. Here in Michigan, because of its industrial history, cars and motors have always been a sort of cult for the whole population. This fetishism finds his most powerful expression in the desire by men, women and kids to build fast cars from wreckages and race in dusty arenas where crowds of adults and children cheer for their gladiators, keeping communities tight in their never-ending challenge to survive.

ABOUT FRANCESCO MERLINI

Francesco was born in Aosta in 1986 and he’s based in Milan. After a bachelor’s degree in industrial design at the Politecnico University of Milan, he completely devoted himself to photography and now he works mainly on personal long-term projects and editorials, always looking for a point of contact between his documentary background and a strong interest for metaphors and symbolism.

In 2016 he was selected by the British Journal of Photography in order to be part of The Talent Issue: Ones to Watch and in 2020 Francesco was shortlisted for the Prix HSBC pour la Photographie. In 2021 he was one of the nominees for the Leica Oskar Barnack Award and in 2023 he was shortlisted at the Sony World Photography Awards.

His pictures have been published in important magazines and newspapers worldwide including Washington Post, Financial Times, Le Monde, Wired, Corriere della Sera and many others while his projects have been featured on renowned photography platforms as American Suburb X and Time Lightbox. Francesco’s work has been exhibited worldwide in solo and collective shows.

Francesco’s last book Better in the Dark than His Rider has been published in 2023 by Depart Pour l’Image. In 2021 he released “The Flood” published by Void. He is currently working on his third book “He’s Come a Long Way That’s My Boy”.

Francesco is a member and the coordinator of Prospekt collective.